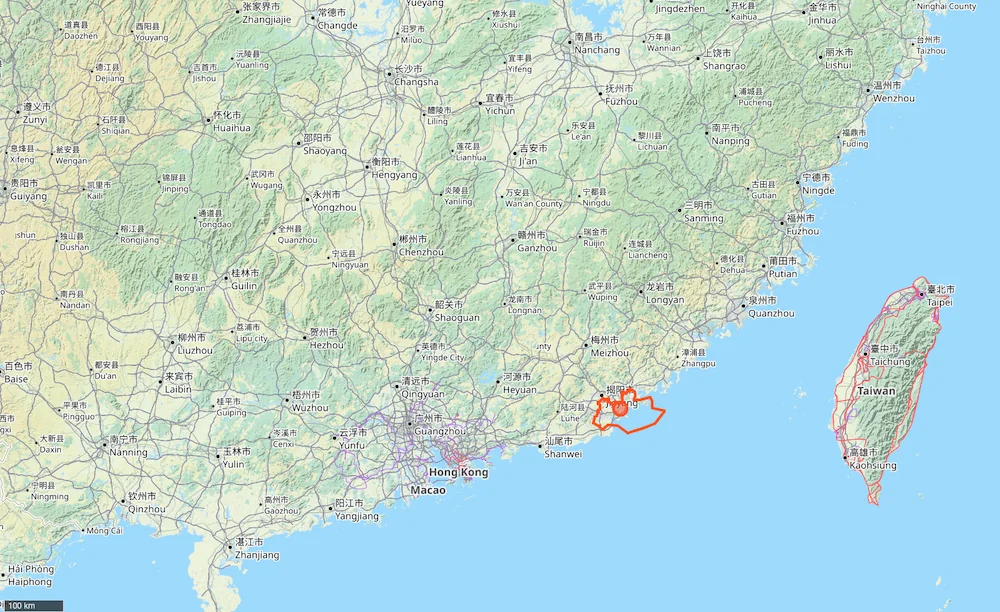

I always wanted to live in the mountains by the sea, preferably on an island. I pictured pine-stitched cliffs dropping straight into a cerulean bay beside a single-street town whose baker greets you by name. I should have specified which sea: the Mediterranean Sea, not the South China Sea. Instead, I landed in Shantou, Guangdong, for a year.

Table of Contents

- How to Buy a Bottle of Water When You Don’t Exist

- The Journey Isn’t Over Yet…

- A Glimpse of the Road Ahead

We were in Shantou because my wife, a scientist, had accepted a year-long research contract at a private university there. My job was simpler: to document the adventure and test the theory that for my work, location and time zones were merely suggestions.

This isn’t just a story about what we saw in China. It’s a story about what it feels like to be an absolute beginner again. It’s about the humbling, frustrating, and ultimately rewarding process of going from a helpless outsider who couldn’t buy a bottle of water to someone who, in small ways, finally belonged.

Google “living in China as a foreigner” and three tribes appear. The first tribe is businesspeople who spend their days shuttling between factories and sealing deals over quaffing baijiu that could strip varnish. I wasn’t one of them. Then come the students: dormitory DJs and cafeteria Casanovas. Their stories focus on university life, parties, and fornication. I wasn’t one of them either. The third group is tourists who come to Beijing, Xi’an, and Chengdu to pose for pictures while wearing rented panda hats. Again, not me.

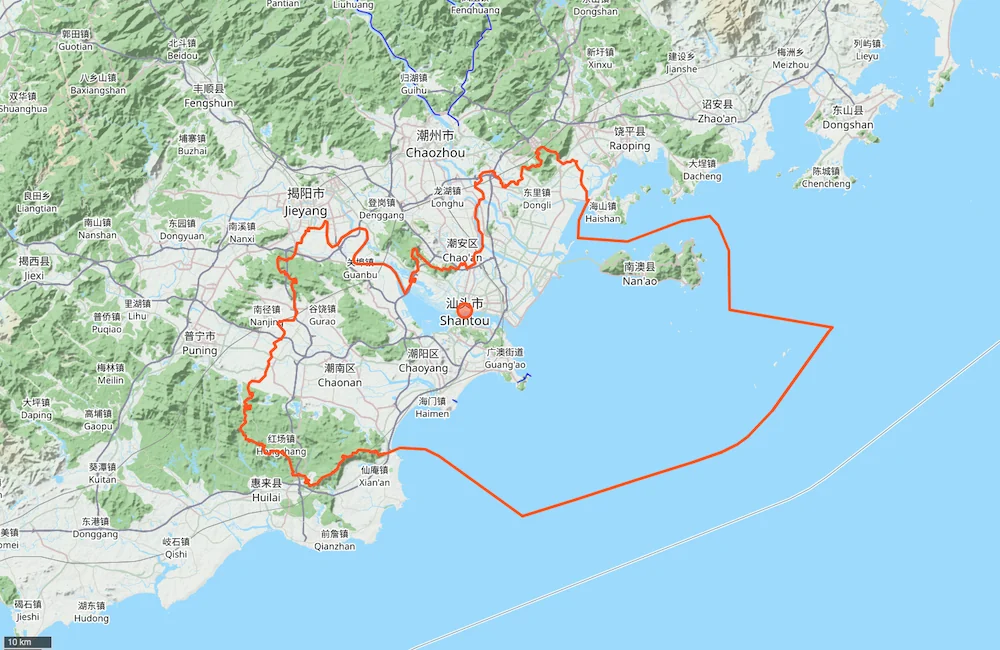

I moved to a third-tier city I hadn’t even heard of until the visa paperwork. Five million neighbors, give or take. A population larger than Ireland tucked into a city I couldn’t find on a map last year. A place where orange construction cranes spear the skyline beside tall, hollow towers with apartments that stay dark for months. Below them, squat older blocks barred by latticework grates. Street-level workshops rasp and clatter well past dusk.

The first day in Shantou made me think of stories told by a vocal minority of Polish people who return from China and catch a bad case of sinotrauma. Back home, they retell every misunderstanding as a personal attack, every interaction with the police as a round-up, and every awful meal as a poisoning attempt. I, on the other hand, fell for the place—for the dawn dim sum steam, for the Mandarin pop leaking from shop radios, for the chaotic order of traffic—a full-blown case of sinophilia.

How to Buy a Bottle of Water When You Don’t Exist

The first few days were a masterclass in helplessness.

My first lesson in Shantou was that the language barrier is a smokescreen. The real obstacle was the information barrier. My wife and I arrived with the right apps, but they didn’t work. To buy a bottle of water, we needed a verified WeChat account. To get verified, we needed a Chinese citizen to vouch for us.

We learned to adapt. Our familiar map apps were useless: Google Maps failed to make its maps resemble actual landmarks, Apple Maps worked fine, but had its data years out of date. We developed a system and juggled two phones. We displayed the Chinese map on one, took a picture of it with the translation app on the other, asked an AI on the second phone how to type the pinyin, and then tapped the alien-looking characters into the first phone’s search bar. It was clumsy and absurd, but it was our first victory. This digital battle was constant. The university’s network thankfully bypassed most of the Great Firewall, but on the go, staying connected to the outside world depended entirely on a foreign e-sim that treated data like a precious, finite resource.

Eventually, the city gave us a rhythm. It started at 7 AM sharp, not with an alarm clock, but with a PT teacher’s whistle from the international primary school next door, blasting music and shouting yī, èr, sān, sì (1, 2, 3, 4). We had no choice but to start our day. We opened the curtains to the view of the mountains surrounding the city, turned on the AC, and joined the students in their forced march into the morning.

We learned the city’s pulse. The mornings were for the giant meat baozi that sold out by 8 AM. For me, the sweltering midday was for remote work and a break in the tiny, free gym in our building. This meant wrestling with time zones, forcing me to choose between waking up at dawn or taking meetings late at night. I always preferred the early mornings, but being far east forced me to learn how to survive working late.

My wife, meanwhile, spent her days in the university’s laboratory, navigating not only her research but also an office culture where public burping and nail clipping were daily occurrences that tested her sanity.

The evenings, as the heat receded, were for exploring. We learned to rely on Didi (China’s ubiquitous ride-hailing app that functions like a more efficient version of Uber) as our reliable escape hatch. The city buses were cheaper and an adventure of their own. Their timetables were an enigma, listing only the start and end times for the day’s service. To know when one was actually coming, we needed a separate app that showed us only the real-time location of the next bus, a surprisingly effective system for a city that lived entirely in the present moment.

And then, slowly, we started to exist. We were no longer just a pale ghost. The campus security guard began to recognize our mangled “Nǐ hǎo” and opened the gate with a wave. The baozi vendor knew which ones we wanted and just waited for us to say how many. The clerk at the canteen knew we always took a chicken wrap with no onion. These were not grand friendships, but they were something more important: small, daily acknowledgements that we belonged to the pattern of the place.

We got used to the city’s character. This was not a tourist town. It was Shantou: an industrial and science hub with five universities, a place the China Daily claimed “drinks more tea than anyone else in China” (and I was doing my best to keep up). It was a working city, unconcerned with charming us, but willing to accept anyone who learned its rules.

And it was a city that constantly tested if we had been paying attention. A trip to the nearby tourist island of Nan’ao drove this home. We took a Didi across the 10-kilometer bridge, visited an ancient well in a small village, and then discovered the truth: Didi works in only one direction. We were stranded.

The bus app said the next local bus was an hour away. It took us to the island’s main tourist draw: a large plaza on a beautiful beach dominated by a monument marking the Tropic of Cancer. It’s a literal line in the sand, a geographical novelty where we could stand with one foot in the tropics and one foot out. From there, another bus took us to the island’s largest town, where, if we were lucky, we could catch the last bus of the day back to the mainland. We were lucky and arrived at the stop 5 minutes before the last bus. It was a perfect metaphor for life here: a series of small, frustrating logistical traps that, once navigated, made us feel like we had truly earned our place.

The Journey Isn’t Over Yet…

Thank you for reading the beginning of my year-long adventure in China.

The full story continues in the complete Kindle ebook, where the real immersion begins. You’ll get the rest of the narrative, including:

-

The story of a village festival where the Ancestor God come to visit, culminating in a deafening fireworks display and a frantic, one-minute race.

-

An evening tea ceremony that revealed a secret pancake recipe so fiercely guarded, it’s only passed on to a son’s wife.

-

Our travels across the country, from the tourist conveyor belt of Xi’an to a city haunted by its own potential in Hong Kong.

-

The hilarious discovery of a geological sex joke told over millennia in the mountains of Danxiashan.

-

The final, quiet moments of understanding that transformed a year of incompetence into a feeling of belonging.

To continue the adventure, you can get the complete, polished ebook on Amazon. It’s formatted for a seamless reading experience on your Kindle, phone, or tablet, so you can take the entire story with you.

Get the book here -> The Sweetness After the Steep: A Year of Becoming a Beginner in China

A Glimpse of the Road Ahead

While the full stories are in the book, I wanted to share some of the sights and sounds from the chapters that follow. Here are the videos from the rest of our journey across China.

The Laoye Festival Dance

The joyous, chaotic dance that welcomed the ancestor to the village, just before the entire square fell silent for prayer.

The ENTIRE Laoye Festival Run (without waiting one hour)

The Distracted Chaoshan Dancers

Who were more interested in the spectators than the dance they performed.