We all know that there is nothing better than a greenfield project. What happens when we begin a new project? There is hope. There are big dreams and new ideas. Now, it is our time! Now, we can write the best code the company has ever seen! Now, we can prove that it is possible to finish a project three months before the deadline!

Table of Contents

What does the project look like after six months? Are we still so enthusiastic? Is everything still brand new and cool? It is not a greenfield project anymore, is it? The bad stuff is not everywhere, but there are places we don’t want to touch. There is code we don’t talk about. What happened?

Bad code is created in the same way as good code, one line at a time.

What makes the difference?

Software architecture

What happened to software architecture? Somehow, we began to pretend we no longer need it. The architecture is not cool anymore. Nowadays, when someone mentions software architecture, people think of ugly UML diagrams produced by the architects. The architects, the people we hate. The ones who are sitting in their ivory towers. The ones who don’t code anymore. We don’t want to be like them. We don’t do “software architecture.”

Obviously, we don’t do it for the right reasons. We are agile. There is no place for software architecture in Agile. Yeah, sure… and don’t get me started on data model design.

The fact is, we always have some architecture. If we don’t produce it deliberately, it will be the result of our random decisions.

We don’t need the cumbersome process of creating UML diagrams. We don’t need oversight of an architect. All we need is one piece of paper and a pen.

We can design the architecture of our software on a napkin while eating lunch. If we don’t like the outcome, we will just throw it away and start over. It is much easier to change the decision when we need to throw away only one piece of paper. Changing our mind gets tough when we need to remove 60% of the code.

Is randomly produced architecture the only problem? We should plan the architecture before starting implementing the code to define our intentions clearly. We must know how the code is going to look like and how it will behave before we write a new line of the production code. Architecture is not enough. We also need tests.

Test driven development

The second problem which turns beautiful greenfield projects into monstrous brownfield nightmare is “upside-down testing.”

Many programmers write tests only because they are expected to do it. They don’t believe in automatic testing. Because of that, the tests are produced after the implementation. Sometimes we think that writing tests slows us down. I have written a blog post about that problem.

How often do we hear: “I have finished this task. Now I only need to write tests, and we can close the ticket.”? Every time we listen to such a statement, we know that the outcome is going to be huge. The production code will be complicated and have double-digit cyclomatic complexity. In the test code, we will see many, many mocks, but there are going to be surprisingly few test function. Just one or two tests that verify everything.

It is not possible to produce such ugly code while practicing TDD. Seriously. Try it, I dare you. Follow the “red-green-refactor” procedure and write a function which has 14 mocked dependencies. You can’t do it. Writing such a terrible code will physically hurt you. Just as much as looking at it hurts.

The enemies of TDD claim that it is just a toy practice. It is suitable for some programming kata exercises, but there no place for it in the “real world.” I used to believe in that too. During one project, I saw that if we “trust the process,” all of our code starts to look like the outcome of a sequence of small, easy programming katas.

Refactoring

What word do we say when we want to terrify a project manager? Refactoring. It scares them because they know that we can’t do it without stopping the world. They know that we may clean up some code, but we will also produce a few more bugs.

How is that even possible? Refactoring is supposed to change the code structure without changing its behavior. We have tests, we can run them after every change and verify whether we have a bug or not.

There are two problems with this assumption. First of all, we don’t trust our tests. We wrote them after the production code was created. We know that there are some untested paths.

The second reason is the fact that we must change our production code and our test code at the same time. There is no other option. We wrote the tests when the production code was ready. We needed to fiddle with them to make them pass. Our test code is coupled with the implementation details of the production code.

That would not happen if we followed TDD. Our production code should behave like a plugin for our tests. We should be able to change the plugin. As long as the new implementation acts as expected, the tests will still pass. If we achieve such level of decoupling, we can refactor the production code any time we want and still be sure that the behavior of the whole application does not change.

Do we care about the tests or are they only the necessary evil? Do we review the tests during code reviews? How many times do we scroll through the tests while reviewing the pull requests?

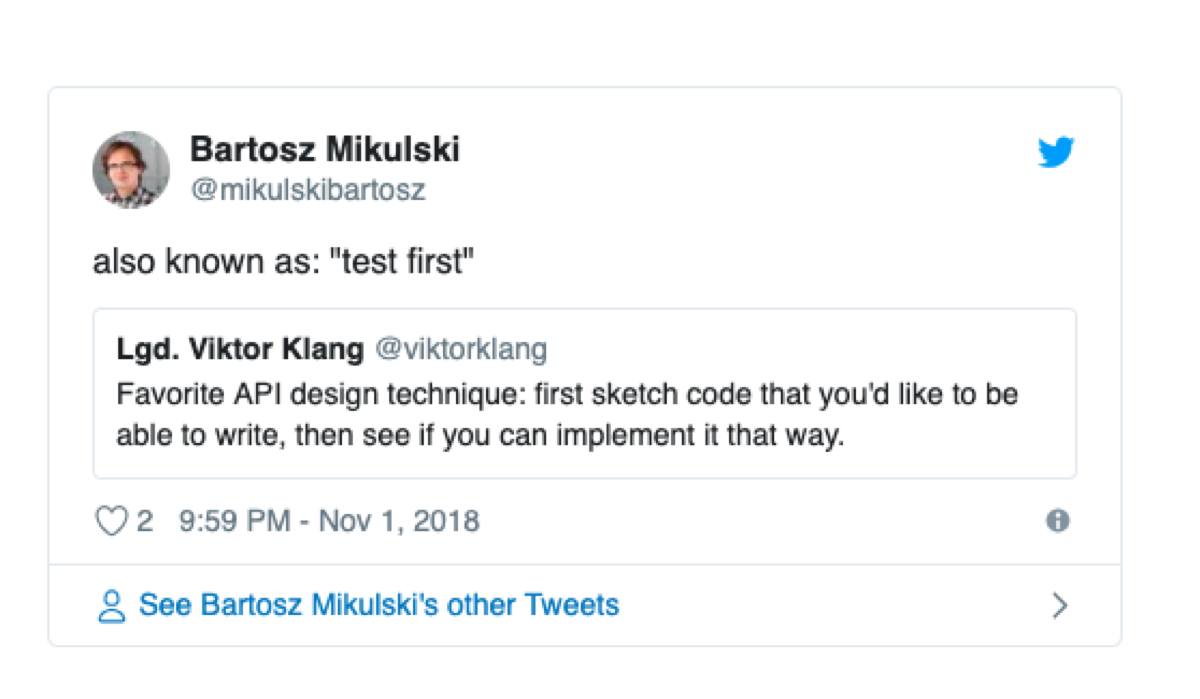

When we don’t follow TDD, tests become a second-class citizen. That should never happen. In the test, we can not only define the expected behavior but also describe the API we want to have. The tests show us how the code is going to be used. If we follow TDD practices, code design happens while writing tests, not when we implement production code.

Ownership

The next problem is the lack of ownership. Who should fix a problem? The person who found it? The person who was the last contributor to the broken project? The person who is affected the most by the problem?

It may be easy to decide when we are talking about a bug. What if the code quality is the problem? What happens when we see a 1000 lines long file, and we have just added another line to it? We found the problem. We are the last contributor to the file. We were affected by the problem. It wasn’t easy to find the right place for the new line of code, was it?

Do we fix the problem? Do we ignore the problem and justify our decision by saying that there were n lines of code, we added the n+1’th line, it is not our problem? The mess was already there. We may even complain about it and do nothing else.

The minor offense of adding a new line of code to already messed up file gets repeated by another person, and another, and another. Two weeks later we have 1000 lines of code.

Teammates That observation leads us to the last problem. Who turns greenfield projects into brownfield monsters? People.

We can complain about teammates who don’t want to learn anything new. We may whine that some of them work 2 hours a day and for the next 6 hours only pretend to work. We may scream every time we see copy/pasted code. We may do many other things, but none of them is going to change anything.

We can’t change people. We can’t persuade them to do something they don’t want to do.

The only way to influence others is leading by example because the only person you can change is you. You are the only person who can stop an awesome project from turning into mud.